Bluets Maggie Nelson Pdf

With Bluets, Maggie Nelson has entered the pantheon of brilliant lyric essayists. Maggie Nelson is the author of numerous books of poetry and nonfiction, including Something Bright, Then Holes (Soft Skull Press, 2007) and Women, the New York School, and Other True Abstractions (University of Iowa Press, 2007). With Bluets, Maggie Nelson has entered the pantheon of brilliant lyric essayists. Maggie Nelson is the author of numerous books of poetry and nonfiction, including Something Bright, Then Holes (Soft Skull Press, 2007) and Women, the New York School, and Other True Abstractions (University of Iowa Press, 2007).

Helena Almeida, Inhabited Painting, 1975.

© Helena Almeida, courtesy Serralves Foundation Collection, Oporto, Portugal

One of the joys of Gwarlingo is meeting art lovers from around the world. Sigrun Hodne and I found each other early in Gwarlingo’s short history, and though she lives in Norway, and I in New Hampshire, I’m constantly amazed by how similar our passions are when it comes to books and art. (If you aren’t familiar with her excellent arts blog Sub Rosa, I encourage you to subscribe.)

Sigrun has studied architecture in Oxford, art history and film in Stavanger, Norway, and literature in Bergen, Norway. (She wrote her Master’s thesis on “Self and Subjectivity in Samuel Beckett’s trilogy; Molloy, Malone Dies and The Unnamable”). She has taught aesthetics in art schools and universities and has done research in language and psychosis. She currently works as an art and literature critic and is attempting to make a living as a writer (no small feat!).

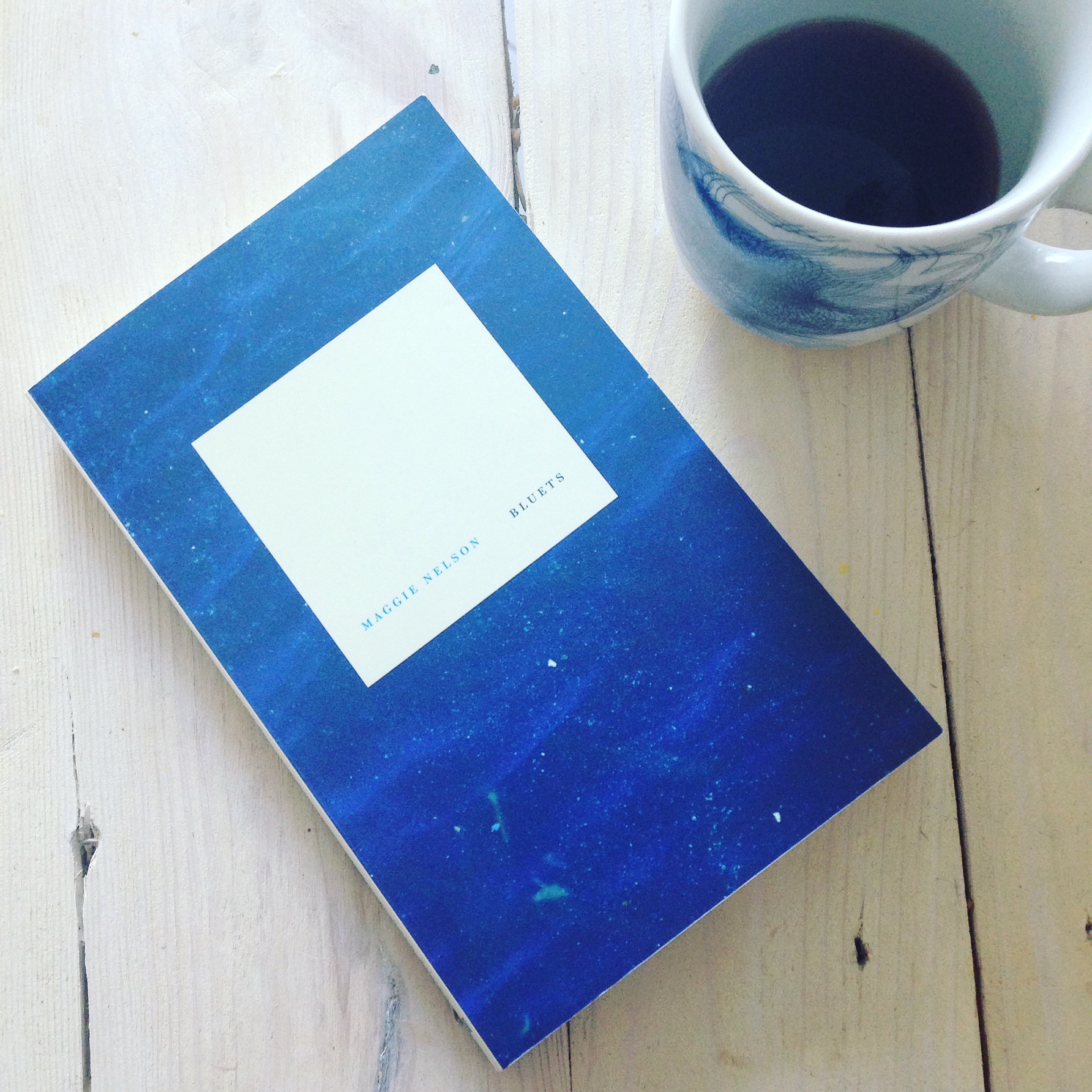

The cover of Maggie Nelson’s Bluets (Photo courtesy Kelli Anne Noftle via theoffendingadam.com)

There has been a strange serendipity with Sigrun across the miles. She will write about a particular artist, book, or subject at the same time I’m also investigating that specific topic.

So it was with Maggie Nelson’s book Bluets (Wave Books, 2009). I was late to the party with this one, but I quickly discovered why this slender volume is considered a literary masterpiece in certain circles (and a cult classic in others). Nelson’s meditation on the color blue, lost love, and depression is a brilliant, effective experiment that defies categorization. This is not only one of the best books I’ve read this year, but one of the best books I’ve read, period.

When Sigrun posted about Bluets on her blog at the very moment I was also discovering Nelson’s publication, I emailed and asked if she would be willing to write a short piece about the book. What follows is her essay, and a special excerpt from Bluets.

A special thanks to Sigrun Hodne, Maggie Nelson, and Wave Books for sharing their work.

Writer, critic, teacher, and blogger Sigrun Hodne in Norway (Photo courtesy Sigrun Hodne)

I Never Knew How Blue Blueness Could Be

by Sigrun Hodne

Lets dive in, give in, lets go where things already have gotten tricky, messy – confused, where words and meanings are bouncing off in different directions, lets have a look at fragment number fifty-one:

51. You might as well act as if objects had the colors, The Encyclopedia says. –Well, it is as you please. But what would it look like to act otherwise?

Indeed, what would it look like to act otherwise?

Maggie Nelson’s book Bluets (Wave Books, 2009) is a bastard, a hybrid, transgressing all and every genre, as they are yet known. Partly essay, partly poetry, it’s a collection of fragments, of quotations, a memoir with a hint of philosophical investigations. Bluets won’t land in any category. But let’s, for the sake of simplicity, call it a long lyrical essay.

A long lyrical essay on the color blue—blue in a public, scientific, and historical sense, but also blue in the most personal sense.

There are several plot-lines: love, pain, friendship, and loss, to mention just a few.

This is how it all begins:

1. Suppose I were to begin by saying that I had fallen in love with a color. Suppose I were to speak this as though it were a confession; suppose I shredded my napkin as we spoke. It began slowly. An appreciation, an affinity. Then one day, it became more serious. Then (looking into an empty teacup, its bottom stained with thin brown excrement coiled into the shape of a sea horse) it became somehow personal.

In art-history, color has often been understood as secondary to form, as something that “fills” the form. In Nelson’s work color take on the lead role (– just as love, the color blue is not an optional supplement, an accidental add-on).

2. And so, I fell in love with a color—in this case, the color blue—as if falling under a spell, a spell I fought to stay under and get out from under, in turns.

A book about the color blue, what a peculiar idea!

13. At a job interview at a university, three men sitting across from me at a table. On my CV it says that I am currently working on a book about the color blue. I have been saying this for years without writing a word. It is, perhaps, my way of making my life feel “in progress” rather than an ash of sleeve falling off a lit cigarette. One of the men asks Why blue? People ask me this question often. I never know how to respond. We don’t get to choose what or whom we love, I want to say. We just don’t get to choose.

Let’s go back to where we started, repeating our initial question: “… what would it look like to act otherwise?”

53. “We mainly suppose the experiential quality to be an intrinsic quality of the physical object” —this is the so-called systematic illusion of color. Perhaps it is also that of love. But I am not willing to go there—not just yet. I believed in you.

“Acting otherwise,” rejecting the systematic illusion of color is, I believe, to abandon a very central social norm: an understanding of the world as a place looking in a certain way – the same way – for each and every one of us. Systematic illusions are the basis of our impression that we share an external reality; it’s the place we meet and interconnect. Systematic illusions make us believe in a common world. ‘Acting otherwise’ is to reject common sense, renouncing the company of humans, and thereby subjecting oneself to alienation and solitude. The extreme consequence of rejecting the systematic illusions of humanity is finally ostracization, solipsism—

—falling silent.

“… But I am not willing to go there—not just yet….”

Bluets, An Excerpt

by Maggie Nelson

14. I have enjoyed telling people that I am writing a book

about blue without actually doing it. Mosty what happens

in such cases is that people give you stories or leads

or gifts, and then you can play with these things instead

of with words. Over the past decade I have been given

Bluets By Maggie Nelson Pdf

blue inks, paintings, postcards, dyes, bracelets, rocks,

precious stones, watercolors, pigments, paperweights,

goblets, and candies. I have been introduced to a man

who had one of his front teeth replaced with lapis lazuli,

solely because he loved the stone, and to another who

worships blue so devoudy that he refuses to eat blue food

and grows only blue and white flowers in his garden,

which surrounds the blue ex-cathedral in which he lives.

I have met a man who is the primary grower of organic indigo

in the world, and another who sings Joni Mitchell’s

Blue in heartbreaking drag, and another with the face of a

derelict whose eyes literally leaked blue, and I called this

one the prince of blue, which was, in fact, his name.

15. I think of these people as my blue correspondents,

whose job it is to send me blue reports from the field.

23. Goethe wrote Theory of Colours in a period of his life

described by one critic as “a long interval, marked by

nothing of distinguished note.” Goethe himself describes

the period as one in which “a quiet, collected state

of mind was out of the question.” Goethe is not alone in

turning to color at a particularly fraught moment. Think

of filmmaker Derek Jarman, who wrote his book Chroma

as he was going blind and dying of AIDS, a death he also

forecast on film as disappearing into a “blue screen.” Or

of Wittgenstein, who wrote his Remarks on Colourduring

the last eighteen months of his life, while dying of

stomach cancer. He knew he was dying; he could have

chosen to work on any philosophical problem under the

sun. He chose to write about color. About color and pain.

Much of this writing is urgent, opaque, and uncharacteristically

boring. “That which I am writing about so tediously,

may be obvious to someone whose mind is less

decrepit,” he wrote.

65. The instructions printed on the blue junk’s wrapper:

Wrap Blue in cloth. Stir while squeezing the Blue in the last

rinsing water. Dip articles separately for a short time; keep

them moving. I liked these instructions. I like blues that

keep moving.

66. Yesterday I picked up a speck of blue I’d been eyeing

for weeks on the ground outside my house, and found it

to be a poison strip for termites. Noli me tangere, it said,

as some blues do. I left it on the ground.

67. A male satin bowerbird would not have left it there. A

male satin bowerbird would have tottered with it in his

beak over to his bower, or his “trysting place,” as some

field guides put it, which he spends weeks adorning with

blue objects in order to lure a female. Not only does the

bowerbird collect and arrange blue objects—bus tickets,

cicada wings, blue flowers, bottle caps, blue feathers

plucked off smaller blue birds that he kills, if he must, to

get their plumage—but he also paints his bower with

juices from blue fruits, using the frayed end of a twig as a

paintbrush. He builds competitively, stealing treasures

from other birds, sometimes trashing their bowers entirely.

A bowerbird building his nest (Photo via duskyswondersite)

69. When I see photos of these blue bowers, I feel so

much desire that I wonder if I might have been born into

the wrong species.

70. Am I trying, with these “propositions,” to build some

kind of bower? —But surely this would be a mistake. For

starters, words do not look like the things they designate

(Maurice Merleau-Ponty).

71. I have been trying, for some time now, to find dignity

in my loneliness. I have been finding this hard to do.

72. It is easier, of course, to find dignity in one’s solitude.

Loneliness is solitude with a problem. Can blue solve the

problem, or can it at least keep me company within it?

—No, not exactly, It cannot love me that way; it has no

arms. But sometimes I do feel its presence to be a sort of

wink—Here you are again, it says, and so am I.

Yves Klein, IKB 79, 1959. Paint on canvas on plywood, 1397 x 1197 x 32 mm. (Photo courtesy the Tate Modern, London)

Installation view of A Bigger Splash: Painting after Performance at the Tate Modern. Includes Yves Klein IKB 79, 1959 © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London, 2012, and Niki de Saint Phalle Shooting Picture, 1961. © The estate of Niki de Saint Phalle (Photo courtesy the Tate Modern)

78. Once I traveled to the Tate in London to see the blue

paintings of Yves Klein, who invented and patented his

own shade of ultramarine, International Klein Blue (IKB),

then painted canvases and objects with it throughout a period

of his life he dubbed “l’epoque bleue.” Standing in

front of these blue paintings, or propositions, at the Tate,

feeling their blue radiate out so hotly that it seemed to be

touching, perhaps even hurting, my eyeballs, I wrote but

one phrase in my notebook: too much. I had come all this

way, and I could barely look. Perhaps I had inadvertently

brushed up against the Buddhist axiom, that enlightenment is

the ultimate disappointment. “From the mountain

you see the mountain;” wrote Emerson.

135. Of course one can have “the blues” and stay alive, at

least for a time. “Productive,” even (the perennial consolation!).

See, for example, “Lady Sings the Blues”: “She’s

got them bad / She feels so sad/ Wants the world to know

/ Just what her blues is all about.” Nonetheless, as Billie

Holiday knew, it remains the case that to see blue in

deeper and deeper saturation is eventually to move toward

darkness.

136. “Drinking when you are depressed is like throwing

kerosene on a fire;” I read in another self-help book at the

bookstore. What depression ever felt like a fire? I think,

shoving the book back on the shelf

Joan Mitchell, Les Bluets, 1973. 110 1/2 x 228 1/4 in. © Estate of Joan Mitchell; Centre Pompidou, Musee national d’art moderne

145. In German, to be blue–-blau sein—means to be

drunk. Delirium tremens used to be called the “blue

devils,” as in “my bitter hours of blue-devilism” (Burns,

1787). In England “the blue hour” is happy hour at the

pub. Joan Mitchell—abstract painter of the first order,

American expatriate living on Monet’s property in

France, dedicated chromophile and drunk, possessor of

a famously nasty tongue, and creator of arguably my favorite

painting of all time, Les Bluets, which she painted

in 1973, the year of my birth—found the green of spring

incredibly irritating. She thought it was bad for her work.

She would have preferred to live perpetually in “l’heure

de hleu,” Her dear friend Frank O’Hara understood. Ah

daddy, I wanna stay drunk many days, he wrote, and did.

146. “When a woman drinks it’s as if an animal were

drinking, or a child,” Marguerite Duras once wrote. “It’s

a slur on the divine in our nature.” In Crack Wars, Avital

Ronell refers to Duras’s works as “alchoholizations”—as

saturated, so to speak, with the substance. Could one

imagine a book similarly saturated, but with color? How

could one tell the difference? And if “saturation” means

that one simply could not absorb or contain one single

drop more, why does “saturation” not bring with it a

connotation of satisfaction, either in concept, or in

experience?

148. The Tuareg wear flowing robes so bright and rich

with blue that over time the dye has seeped into their skin,

literally blueing it. They are desert nomads who were famously

unwilling to be converted to Islam: thus their name.

Some American Christians have been bothered by

this idea of a blue people abandoned by God living in the

Sahara, herding camels, traveling by night, and navigating

by the stars. In Virginia, in 2002, for example, a group of

Southern Baptists organized a day of prayer exclusively

for the Tuareg, “so that they will know God loves them.”

149. It should be noted that the Tuareg do not call themselves

Tuareg. Nor do they call themselves the blue people.

They call themselves Imohag, which means “free

men.”

150. For Plato, color was as dangerous a narcotic as poetry.

He wanted both out of the republic. He called painters

“mixers and grinders of multi-colored drugs,” and color

itself a form of pharmakon. The religious zealots of the

Reformation felt similarly: they smashed the stained-glass

windows of churches, thinking them idolatrous, degenerate.

For distinct reasons, which had to do with the fight

to keep the cheap, slave-labor crop of indigo out of a

Western market long dominated by woad, the blue-dye

producing plant native to Europe, indigo blue was called

“the devil’s dye.” And before blue became a “holy”

color-which had to do with the advent ofultramarine in

the twelfth century, and its subsequent use in stained

glass and religious paintings—it often symbolized the Antichrist.

177· Perhaps it is becoming clearer why I felt no romance

when you told me that you carried my last letter with you,

everywhere you went, for months on end, unopened.

This may have served some purpose for you, but whatever

it was, surely it bore little resemblance to mine. I

never aimed to give you a talisman, an empty vessel to

flood with whatever longing, dread, or sorrow happened

to be the day’s mood. I wrote it because I had something

to say to you.

Bluets Maggie Nelson Pdf

About Maggie Nelson

Maggie Nelson is the author of four books of nonfiction: Bluets (Wave Books, 2009), Women, the New York School, and Other True Abstractions (University of Iowa Press, 2007), The Red Parts: A Memoir (Free Press, 2007), and The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning (W.W. Norton, 2011). Nelson is also the author of several books of poetry, including Something Bright, Then Holes (Soft Skull Press, 2007), Jane: A Murder (Soft Skull ShortLit) (Soft Skull, 2005), The Latest Winter(Hanging Loose Press, 2003) and Shiner (Hanging Loose, 2001). She has been the recipient of an Arts Writers grant from the Creative Capital/Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship for Nonfiction. She has taught writing and literature at the Graduate Writing Program of the New School, Wesleyan University, and Pratt Institute of Art. Nelson currently lives in Los Angeles where she teaches on the BFA and MFA faculty of the School of Critical Studies at California Institute of the Arts.

You can purchase Bluetshere, at your local bookshop, or directly from Wave Books.

Please Help Gwarlingo Remain Ad-Free

Thanks to all of the readers who have contributed to the Gwarlingo Membership Drive. 136+ Gwarlingo readers have contributed so far and $12,350 of the $15,000 goal has been raised. If you haven’t donated yet, you can check out my video and all of the member rewards, including some limited-edition artwork, here on the Gwarlingo site.

Don’t need a reward or official acknowledgement for your gift? Want to keep the donation process simple? Click here to make a donation of your choice. (Good karma included!)

Subscribe to Gwarlingo

Stay up on the latest poetry, books, and art news by having Gwarlingo delivered to your email inbox. It’s easy and free! You can also follow Gwarlingo on Twitter and Facebook.

Also, check out the Gwarlingo Store–a handpicked selection of books of interest to writers, artists, teachers, art lovers, and other creative individuals. A portion of all your purchases made through the Gwarlingo Store portal, benefits Gwarlingo.

Bluets © Maggie Nelson. All Rights Reserved. These excerpts appear in Bluets(Wave Books, 2009) and were reprinted with permission from the author and Wave Books. Maggie Nelson biography also courtesy of Wave.

Bluets is a book by American author Maggie Nelson, published by Wave Books in 2009. The work hybridizes several prose and poetry styles as it documents Nelson's multifaceted experience with the color blue, and is often referred to as lyric essay or prose poetry.[1][2]It was written between 2003 and 2006.[3][4]The book is a philosophical and personal meditation on the color blue, lost love, grief and existential solitude.[4][1][5][6] The book is full of references to other writers, philosophers and artists. The title refers to the painting Bluets by the artist Joan Mitchell.[4]

Structure and subject[edit]

Bluets is a 'formal experiment'[3]that contains an arrangement of 240 loosely-linked prose poems which Nelson refers to as 'propositions'.[4][3] Each proposition is either a sentence or a short paragraph, none longer than two hundred words; the book totals some nineteen thousand words.[1] The propositions are arranged neither chronologically nor thematically, but in each one, Nelson produces links between different blues and their associations.[4][1] Nelson shuffled the propositions around 'countless times'[7] before arriving at their final order. The critic Thomas Larson refers to the structure as a 'nomadic mosaic': 'Its structure is built by pulling away from the core and by keeping attached to the core. The goal (if there is one) is nomadic, a sort of nomadic mosaic. As one reads, the book, despite its progression, loses its linearity and feels circular, porous, a tad unstable'.[1]

The three main topics that Nelson investigates within Bluets are her affinity to the color blue; the loss of her lover, whom she calls 'the prince of blue'; and her relationship to a close friend rendered quadriplegic after an accident.[1][4] However, most of the text is an analysis of her reading, often referring to other writers' reflections on the color blue, art, literature, philosophy, emotion and female desire.[1][4][3] The references include Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Sei Shōnagon, Catherine Millet, Chögyam Trungpa, Isabelle Eberhardt, John Berger, and Marguerite Duras. The exploration of the color blue is particularly inspired by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Theory of Colours, and Ludwig Wittgenstein's Remarks on Colour.[8]

Reception[edit]

Bluets has been referred to as a 'cult favourite'.[3]

Writer and critic Hilton Als praises Bluets as a new form of classicism: 'Balancing pathos with philosophy, she created a new kind of classicism, queer in content but elegant, almost cool in shape'.[9]

References[edit]

- ^ abcdefgLarson, Thomas. 'Now, Where Was I? : On Maggie Nelson's Bluets'. triquarterly.org. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^Lerner, Ben. 'BEYOND 'LYRIC SHAME''. lithub.com. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ abcdeLaity, Paul. 'Maggie Nelson interview: 'People write to me to let me know that, in case I missed it, there are only two genders''. theguardian.com. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ abcdefgFrancis, Gavin. 'Bluets by Maggie Nelson review – heartbreak and sex in 240 turbocharged prose poems'. theguardian.com. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^Schmid, Katie (June 24, 2014). 'The Last Book I Loved: Maggie Nelson's Bluets'. The Rumpus.

- ^Cooke, Rachel. 'Maggie Nelson: 'There is no catharsis… the stories we tell ourselves don't heal us''. theguardian.com. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^Nelson, Maggie (October 1, 2009). Bluets. Seattle: Wave Books. p. 74. ISBN9781933517407.

- ^Myers, Gina (2009). 'Bluets by Maggie Nelson'. Book Slut.

- ^Als, Hilton. 'Immediate Family Maggie Nelson's life in words'. newyorker.com. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

External links[edit]

Bluets Maggie Nelson Excerpt

- Maggie Nelson reads from Bluets at the Festival of Poets. September 22, 2008.